Caught Between Two Cultures

Current Mayor, Andrew Judd is about to step down from his one and only term, after recognising his support for a Maori ward was not a popular option for the New Plymouth District Council’s constituents.

Describing himself as a “recovering racist” Judd’s inadequacies with New Zealand’s indigenous culture is something many Pakeha can identify with. But what about Maori people from a similar era?

How are they coping with a society searching for the best way to achieve multi-cultural nirvana?

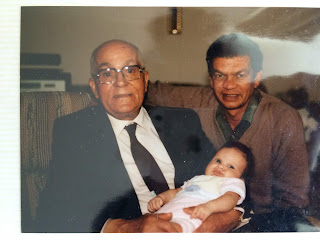

New Live writer Michelle Robinson speaks with her father-in-law Steve Robinson about finding his identity as a modern day Maori in New Plymouth. He speaks about wanting to reconnect with his culture after finding success following the Pakeha way of life, and how he reckons both cultures need to be embraced in equal measure for society to move forward.

From sleeping on the dirt floors of his family marae to owning several properties, New Plymouth man Steve Robinson is a man of two worlds.

Taranaki born and bred, Tutahi Aranga Steven Francis Robinson, 66, grew up in an era where the marae provided the necessities of home.

It was a life of simplicity where the cousins all shared beds or slept on mattresses on dirt floors softened by bracken fern and hay. Fruit and vegetables grew in the garden of Ngarongo Marae, South Taranaki, and milk came fresh from a neighbouring farm.

It’s a far cry from the life Steve and his wife Kaye gave their four sons, who Steve says fit into both Maori and Pakeha worlds “without any hassles”.

There’s a hint of a smile on his lips when he speaks his next words.

“My grandmother, my kui, she said ‘the only way to beat Pakeha is to marry them’.”

He backpedals. “One way to get along with and understand the Pakeha culture is to marry into it. It’s not always a view held by many in either culture.”

Today Steve and Kaye personally own several investment properties and Steve is chairman of his hapu (family group) Ngati Tu Whanau trust board, overseeing 80 hectares of prime farmland with shares owned by some 40 families.

The position on the board is something he holds in high regard. “We are trying to increase the financial base to benefit the growing families.”

He would love to see many marae fully utilised to house and feed struggling families, providing them with the life skills and training to make a difference in society.

“If we can utilise the land not being used, that is marae, crown and council land, people may see a different Maori.”

In managing the hapu’s shares alone, it can be tricky to make contact with the new generation of a family when an elder dies, Steve admits.

Connections are being lost, ties to the land, forgotten.

To be successful in life, Maori must embrace their own heritage and European culture in equal measure, Steve says. “Until we all learn to blend the two worlds together, there will always be separation.”

On meeting Steve, one has the impression he is a confident man. He smiles and talks to strangers like they’re old friends. Maori are greeted with the iconic raised eyebrow, chin up, head nod. There are always hugs. He’s the guy who seems to know everyone. When he speaks, his statements are broad and chummy, making those with him feel like he’s on their team.

Yet when you dig deeper, there’s an almost shyness or apologetic nature about Steve. He’s reluctant to speak out of turn lest he causes offence or appears arrogant.

An example of this is that he takes little credit for what he has achieved for his community over the years. He’s fostered or “whangaied” 15-odd kids with Kaye, spent years teaching bush survival and life skills to youth and taught Maori both at community college level and primary school.

He attributes the success that’s allowed him to give back, squarely at the feet of “the Lord Jesus Christ”. He’s been a Christian for years, but he hasn’t always felt confident enough to proclaim it in public.

Despite his traditional upbringing, Steve grew up with little understanding of the history of the land – the Taranaki land wars of the 1860s, the unjustified land confiscations of the 1880s, the key Maori defenders.

Steve sympathises with Mayor Andrew Judd and councillor Howie Tamati’s sentiments about the lack of Maori place names in Taranaki. “I didn’t know about the Parihaka wars until I returned to Taranaki in 1985, how sad is that?

“It would be good to have a few place names with our own famous warriors, Te Whiti, Tohu, Titokowaru,” Steve says.

“They got beaten. They just brought more and more men from England, I suppose.”

As far as that other polarising issue of whether or not the New Plymouth District Council needs a Maori ward, Steve argues that Maori are putting their hands up for the job but they’re not getting recognised.

He believes Maori could do more to put themselves forward and vote for eachother to get onto council. But he also believes there is a lingering stigma against Maori having a voice on ‘Pakeha issues’.

“There are too many Pakeha who are still afraid that Maori will dominate.”

Steve can name three Maori off the top of his head who would be “excellent” for the job of councillor.

Dion Tuuta, former CEO of Parininihi ki Waitotara (PKW), a group that manages 15 Taranaki dairy farms; Hayden Wano, CEO of health and social services provider Tui Ora and former Taranaki District Health Board chairman; and Taranaki iwi leader and CORE Education senior manager Wharehoka Wano.

“But do they have the time?”

And herein lies the problem. Those who fit the bill are up to their eyeballs in other boards, trusts and community projects. Their focus is stretched. Not only do they have to appease Maori, but also Pakeha if they want to be counted.

In a way, Steve can relate. “I spent most of my life trying to adjust to the European way of life.”

Would he run for council?

“If someone thought I could contribute to the betterment of not only Maori but also Pakeha, then yes.

“I will not work for just one people.”

Back on the marae, Steve hardly ever got sick. He was rugged up in tidy hand-me-downs and in winter the coal range on which the whanau cooked ran 24/7.

The kids rode on horseback or walked the five kilometre journey to Normanby Primary School. At home there was always singing and laughter to be heard as the kids sat with the nannies while they worked in the garden. Steve’s first job as a teenager was delivering fruit by pushbike.

On the marae, the children made their own toys and possum traps out of flax, raupo, lancewood and nails.

Steve remembers being given a prized wind-up tin crocodile. “It was the only toy I remember having.”

Steve left Taranaki for a panelbeating apprenticeship in Christchurch at age 17 where he later found work in the railroads of Ashburton.

It was there where Steve first attempted to reconnect with his language, even though it hadn’t actively been encouraged by his family. There was a lingering attitude among some Maori in the 1960s and ‘70s that the Pakeha life was the only road to success.

Over the years Steve’s driven trains, buses, cranes, forklifts, has worked at Bunnings and done retrofit double-glazing. Today he’s a property owner and is back working on the car yards.

You could say he’s a salt-of-the-earth, blue collar Maori who found a way to make both cultures work for him and his community. But it’s far from a perfect mix.

“I had a desire to communicate in my own language,” he says.

“Yet I don’t feel confident at whaikorero (speaking Maori) in front of my group, it’s a sad indictment. As I get older, I’m losing it. I’m not in an environment to continue speaking it. It makes me frustrated.

“I’ve been asked to be a kaumatua but I won’t accept,” he says.

“Before then, in all honesty, I want to be able to whaikorero. To stand on the paepae and speak eloquently and wisely.”

Comments

Post a Comment